Yoruba culture and its relationship with death and grief

Death is not a strange phenomenon in Yoruba culture. From ancient times, there has been the understanding that being born inevitably implies dying. An ancient proverb expresses this clearly:

Àwáyé má kúkòsí, òrun nikan láré má bọ̀

Everyone born into the world is destined to die; only existence in Òrun is permanent

This view invites us to perceive death not as an absolute rupture, but as part of a larger cycle of existence. And that is why, in Yoruba tradition, death should not be taboo: it must be acknowledged, discussed, respected — even when the topic makes us uncomfortable.

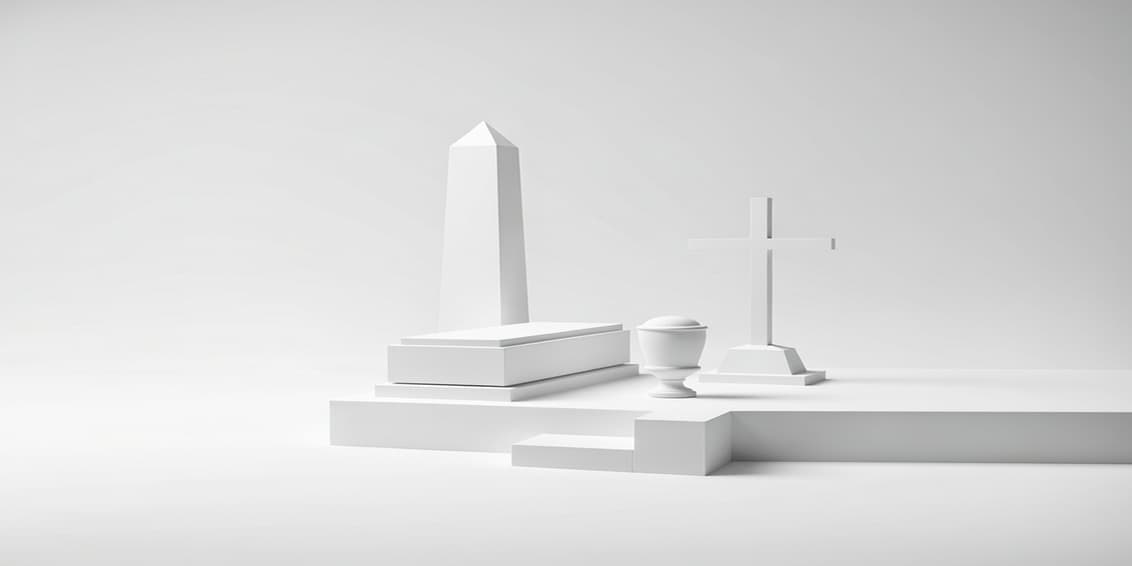

What death "is" in the Yoruba worldview

In Yoruba cosmology, the human being is not reduced to the physical body. There is a structure of existence that involves material and immaterial components, and death is understood as separation, not annihilation.

In classical readings of Yoruba religion and philosophy, the person is described by elements that relate to each other, such as:

- Ara (body): the physical part, the "house" of existence in Ayé, which is buried and returns to the earth.

- Òkàn (heart): not just the physical organ, but also an invisible dimension associated with emotional life, thought, and action.

- Emi (vital principle / spirit): life itself, attributed to Olódùmarè (sometimes referred to as Elemi, "owner of life").

- Eemi (breath / vital breath): linked to the act of breathing; when the breath ceases, the transition is marked.

- Orí (the "inner head", Orí inú): the core of destiny, personality, and existential direction — often understood as that which guides the person before birth, during life, and on the return after death.

For this reason, when death occurs, it is understood that the body decays, but the essence does not disappear: it continues its journey toward Òrun, returning to the source from which it came.

Death, ritual, and the reorganization of life

Death is not merely "an individual event." In any culture, it disrupts bonds and requires reorganization — and this is even more visible in spiritual traditions.

Funeral rites and mourning customs fulfill important human and spiritual functions, such as:

- giving destination to the body,

- facilitating the passage of the spirit / soul to its next stage,

- and reorganizing the network of social and affective relationships that has been interrupted.

That is why talking about death is not morbid: it is a gesture of communal and spiritual maturity.

Communication with the dead, ancestry, and continuity

In Yoruba tradition, it is also acknowledged that there is communion and communication between the living and the dead — and that those who have departed can influence, guide, protect, or even disturb, depending on the context, the character, and the type of death.

This point is delicate: it does not need to be reduced to "proof" or "disbelief." For many people of axé and other traditions of the diaspora, the presence of ancestors is something experienced in practice: in dreams, signs, intuitions, rites, and collective memory. Still, the tradition can acknowledge the experience without turning everything into literalism.

"Good death" and "bad death" (and why this changes everything)

Yoruba culture also distinguishes ways and qualities of death. This is important because it impacts:

- which rites can or cannot be complete,

- how the community interprets the passage,

- and how the relationship with ancestry is understood.

There are deaths considered "good" (for example: long life, character considered worthy, descendants, and complete rites), and deaths considered "bad" or premature (òkú òfò, "death out of time"), associated with tragedy, rupture, or specific conditions. In many traditional readings, certain "difficult" deaths may not receive the same full rite, and are not always understood as an immediate path to ancestral status.

This point requires care: it is not meant to "judge anyone's life" — it serves to recognize that the tradition thinks about death with symbolic, ethical, and ritual criteria.

Atúnwáyé: the return to life and its forms (without simplification)

Yoruba tradition strongly upholds the belief in Atúnwáyé — often translated as reincarnation or return to life. But this theme is not simple or uniform: it appears in different forms, with nuances of region, lineage, and interpretation.

Carefully, we can cite three expressions that recur frequently:

- Ìpadàwáyé: the "return to the world" associated with the ancestor's rebirth in the lineage (the most common form in popular transmission).

- Abíkú: "born to die" — children who would die repeatedly to the same parents; the tradition describes spiritual bonds and specific rites that would seek to break the cycle.

- Àkùdààyà: "one who died and returns to live" — associated with accounts of reappearance, reexistence elsewhere, or return under exceptional conditions.

An important distinction here: not every return is understood as "being reborn in a baby." Some traditional readings allow for brief reappearances, interventions, appearances in dreams, or cyclical patterns on significant dates — as if the spiritual presence reaffirmed itself to guide and demonstrate continuity.

Names as cultural evidence (lineage and return)

A very rich (and accessible) detail is how the belief is inscribed in language and names. In Yoruba culture, names like:

- Bàbátúndé ("the father has returned")

- Yétúndé ("the mother has returned")

can express the sense of ancestral return in the lineage, reaffirming a vision of family that spans time.

How is a "return" recognized?

Popular tradition presents justifications such as:

- physical and behavioral resemblance to ancestors,

- marks that would reappear in subsequent births in cases associated with Abíkú,

- and accounts of transferred memory (children narrating experiences linked to deceased persons).

This does not need to be treated as "scientific proof." It can be treated as cultural and spiritual epistemology: a way of perceiving and interpreting reality that organizes the world with internal coherence.

Òrun rere and Òrun àpààdì: morality and destiny after death

Some traditional approaches describe Òrun with distinct dimensions, often presented as:

- Òrun rere (the "good Òrun")

- Òrun àpààdì (an Òrun associated with punishment/negative condition)

This language points to an ethical principle: life has weight, character has consequences, and death is not disconnected from morality. In many readings, ancestral status is linked to a life considered dignified and to appropriate rites.

A phrase that protects life: "the present is more important"

Even while upholding the idea of return, Yoruba culture frequently reaffirms that the present life takes primacy.

A much-quoted proverb summarizes this:

Ayé yìí ni a ó kọ́sẹ̀ kí a tó ṣe Òrun

We will live in this world first, before living in the other world

And there is also an expression that carries this ambivalence:

Àṣẹhìnwáyé ẹni, bí ẹ̀bùn ló rí

Someone's return to life may seem like a "gift," but it can also sound like a kind of deception

This prevents the belief in return from becoming escapism. The lesson is clear: do not live a lesser life expecting another life.

Mourning: where tradition explains, but does not remove

There are things that tradition explains — and there are things it does not remove.

No cosmology eliminates the feeling of loss. Mourning continues to be real, intimate, and non-transferable. That is why Psychology can be useful here as a complement: not as a substitute for tradition, but as human support for traversing pain.

The stages of grief are often described as:

- denial,

- anger,

- depression,

- acceptance,

not as a rigid ladder, but as an approximate map. Each person traverses this in their own time.

And it is important to remember: death does not involve only the one who departed. It directly involves those who lived with the person and, indirectly, all who will need to fulfill rites, welcome, support, and reorganize life.

Initiation, foundation, and hierarchy: who dictates the steps

For those who live African diaspora religions, this is an essential care: no one "decides alone" what to do in the face of a death from a ritual perspective.

Respecting initiation and foundation is recognizing that:

- there are specific procedures,

- there is communal ethics,

- there are people responsible for conducting,

- and there is the right timing for things.

The one who guides your religious life — respecting the decisions defined by your Orishas and following the foundation of the house — is who will indicate the steps when someone passes from Ayé to Òrun.

The Passage

Talking about death, within Yoruba culture and the traditions of the diaspora, is not a lack of faith. It is responsibility. It is awareness. It is respect.

May we speak about death without fear, live mourning without haste, and honor both those who depart and those who remain — with humanity, with silence when needed, and with firmness when care demands it.

Axé,

Olórun bùsí fún ọ